|

Prado, Madrid

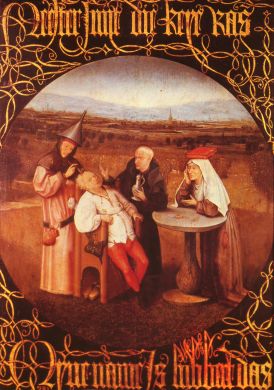

Museo alemán de epilepsia en Kork www.epilepsiemuseum.de |

The discovery of the Greek physician Claudius Galenos (129 - 199) that a death does not always occur when the brain is opened up, led to the idea that the "evil falling sickness stone" could be surgically removed. However, as early as 900, the Persian physician Rhazes was criticising this method: "Some wonder doctors claim that they can heal the falling sickness, they make a cross-shaped opening at the back of the head, and pretend to take something out which they had been holding in their hand...!" |